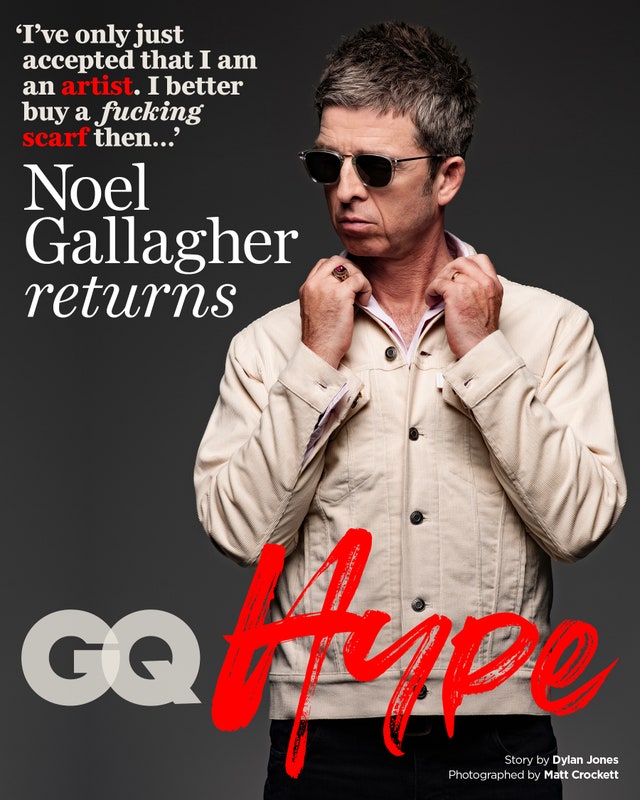

Noel Gallagher confess to GQ Magazine that “A lot of the early songs were actually written for Oasis”.

Noel Gallagher has just announced is return with a new single and a greatest hits of his three solo records.

Speaking with GQ Magazine UK, the Mancunian singer has revelead that a lot of NGHFB early songs were written for Oasis.

Noel, I’m not going to ask you any questions about your brother, but going all the way back, you’ve just come out of Oasis, the biggest band of your generation, and you’re sitting at home wondering what to do. What was going through your mind?

I was only sure of one thing and that was that I was going to do nothing. So I took a full year out and wasn’t really thinking of anything, which I would normally do at the end of the tour anyway. We would take quite a substantial amount time off and get back to normal life. Then after about a year I went to bed one night, not really thinking about anything and then woke up the next day and was like, “Right, let’s make a record.” So, I didn’t really have a band or the band’s name until the record was finished and we were due to come out, so I kind of took my time with it. I didn’t rush into anything. I didn’t really know until I’d recorded the album whether I was going to be singing. I was just going to do these songs and see how they all felt and they all felt great. And I was like, “Well, I better think of a fucking name for the band.”

The name was inspired by Jefferson Airplane, right?

Yeah. It’s such a stupid story. I remember driving past Shepherd’s Bush Empire one night coming home from the studio and I was trying to visualise my name in the lights and I thought, “No, I’ve got to come up with another name.” [As he says himself, his name’s not exactly Ziggy Stardust.] I was using the dishwasher the next day and the radio was on and I don’t know what station it was but they played something by Peter Green’s Fleetwood Mac and then they played the Jefferson Airplane cover of “High Flying Bird”. I thought Fleetwood Mac, something like that, and then thought high flying birds and did a quick check to see if it was copyrighted and it wasn’t and I was like, “Great.” I didn’t think too much about it after that, really.

Why the aversion to just going solo?

I suppose it was a confidence thing. Because coming off the back of something so significant and having such a strong identity, I guess part of me didn’t want to give the impression that I was just going to go out on the road and do the hits. And that was it. So I suppose it was a bit of a halfway house. I kind of fudged it a little bit, really, as it’s like a band name, but it’s got my name in it. And sounded cool. I wrote it down on various fucking things and kind of stared at it and thought, “Actually, it looks quite cool. Let’s go with it.”

I’ve read in various interviews that you said you had to change the way you wrote songs. Is that true?

Completely. When you’re writing for a band that’s become a brand and a huge fucking business – and this is only with hindsight, as I didn’t realise this at the time – you’re kind of writing with the weight of the brand hanging over you. The songs have to sound a certain way to sell 70 million records and you’re not going to just throw it all up in the air on a whim. A lot of the early High Flying Birds songs were actually written for Oasis, but as I’m not a brand, and as High Flying Birds is not a brand, I could do whatever I wanted. When you’re Metallica, or Red Hot Chili Peppers, the masses expect a certain kind of thing from you. Most big bands never stray from the path and Oasis had got like that. You know, this is what we do: there’s a certain sound and there’s a certain venue that we play and the music has to fill that venue. So once I had shaken that off, it was really fucking liberating as a songwriter.

I remember Bono said once U2 always worried in the studio when someone said what they were doing was “interesting”, as you couldn’t do that with U2; you’ve got to write U2 songs that sound great in a stadium.

That’s true, although they’re probably the most flexible of all those big bands, where they do kind of veer off from time to time. When I was on tour with them, I told Adam Clayton I was still getting a lot of shit from Oasis fans because I was using synthesisers and he said they had the same thing with Achtung Baby. I said, “Yeah, but you didn’t have social media to contend with so you had no idea what people were saying.” I’m not on social media myself, but my business is, and the abuse from Oasis fans has got worse as it’s gone on. But you can’t let it dictate what you do.

I did the stadium rock thing once and I don’t think I’m capable of doing it. Halfway through my first tour, I’d sold out the O2 and it didn’t really sit that well with me. Because a) I felt I hadn’t earned it and b) I thought people were coming to see the guy from Oasis – and he better be doing these fucking eight songs! Which, of course, I didn’t and I have never played there since. I’m more comfortable in theatres, where you can engage with an audience slightly. Whereas in arenas, an arena crowd will expect a certain kind of delivery. Which I’m not capable of doing.

For years, Paul McCartney wouldn’t talk about The Beatles, but the older he gets, the more ownership he takes. When you left Oasis, did you talk to anyone who had been through something similar?

The only person I asked was Paul Weller, who is one of my oldest friends, and his attitude towards all this was “Fuck them”, which was great. So it only dawned on me further down the line that actually the High Flying Birds is my Style Council. When I saw the documentary about them recently, it brought it all into focus: they had a black girl in their band and I have a black girl now and a French girl and so on. Jam fans were saying to Weller, “What the fuck are you doing?” And Jam fans and Oasis fans are kind of cut from the same cloth, very fucking laddish and identity driven.

It’s really character building when you play a song from Oasis, which everyone knows and the place goes fucking apeshit, and then you play your new stuff and there’s clearly a fucking drop-off in people digging it. And in between those songs, people are constantly shouting out for stuff that you wrote 20 years ago. But you either sink or swim and you have to actually look these people in the eye and say, “Fuck them.” Weller never played anything by The Jam that I’m aware of for about ten years and even then he wouldn’t play “A Town Called Malice”. I feel that if I play “Don’t Look Back in Anger”, “Wonderwall” and “Half The World Way” and that still isn’t enough, I’m thinking, “Aren’t enough? What more do you want?”

What did you need to achieve that you hadn’t already achieved in Oasis?

I’d got to 43 and was in a band that changed the world. But it was built on arguing and I was like, “I’ve got two fucking kids.” This was the bit where I was supposed to be enjoying myself. I should have been worrying about buying a fucking beach, not arguing about who was supporting us. Travelling the world and having 5,000 or 20,000 people fall in love with you simultaneously every night is the greatest thing you could ever do. But not when you’re fighting on the way to a venue about the tour manager. It was soul destroying and I wanted to be happy. Some people think what I do is fucking atrocious and some think it’s better than what I used to do. So it’s all about the listener.

When I got to the third album, Who Built the Moon?, which was produced by David Holmes, I thought it was probably a good time to throw it all up in the air, as I’d done two guitarish albums. Also I didn’t want a load of other guys on stage. I’ve always had girls singing on my solo stuff, so it became a natural thing. When we were in America at some fucking thing, and we were all crammed in the same dressing room, girls and boys, and our girls are putting on make-up and all the lads are sitting there talking about football, one of them said to me, “I bet you never thought we’d get like this did you?” I was like, actually, this is what I was planning on it being like, like a travelling circus.

Even though you’re not on social media, isn’t there a temptation to just peek over people’s shoulders to see what people are saying?

No. As you well know, no good ever comes from it. But you wouldn’t be human if your new song was out there and you didn’t think, “I wonder what people are saying.” To be honest, it didn’t really bother me one way or the other until “Holy Mountain” came out. I spoke to someone from my office back here and asked what the reaction had been like. And they said it was mixed. I said, “Well, it’s always mixed.” And they said it was “very” mixed.

When I first met David Holmes, the way he worded how we were going to make this record was crucial. He said, “Look, what you do with that acoustic guitar is amazing. Everyone fucking loves it. But don’t you want to make some music that’s the kind of music you listen to?” I thought, “Yeah.” And he’s pulling out all these records, all obscure, fucking Kraut rock, and he’s going, “What do you think of that?” I fucking loved it. And he’s like, “Right then, we’re going to do a track like that.” And it’s very liberating to hear that from a producer, because I’ve worked with producers before and they know the record they want you to make before they come to the meeting, because it benefits them. Everything that I would do, that even remotely had a hint of traditionalism to it, he’d say. “No. Do it again.” You know, I remember writing eight choruses for one song once and each one was getting better and I was thinking, “What the fuck does this guy want?” And I got to the ninth one and he said, “That’s the one.” It was great to be pushed like that. So the next album should be fucking great.

How do you take criticism? Having been an autonomous songwriter from the off, are producers the only people you listen to now?

I never used to listen to anyone when I was in Oasis because of the brand and because of the band. I remember doing Standing On The Shoulder Of Giants with Spike Stent and there was a drum machine in the control room and I said, “Spike, you won’t be needing that. It’s more trouble than it’s worth.” I’ve never seen a person so pale in my life. But once I stepped outside of that, I became open to it all. I’ve cowritten about six songs in lockdown with people there is no fucking way I would have got involved with in the old days. I guess it’s because I’m completely satisfied with how Oasis sits now and what its legacy is, because I’ve always got that. And in a worst case scenario, if I end up doing what people want me to do, which is all the Oasis songs and make a great life out of it, it’d be fucking great and bring people a lot of joy. But as an artist, I don’t want to do that. Because I’ve only just accepted that, actually, I am an artist.

Why has it taken so long?

Because it wasn’t the type of thing you’d say on a council estate. I will always be the lad from the council estate with the guitar who knew how to play “She Loves You”.

But that was years ago.

Yeah, of course. But when I was in Oasis, if anyone said you’re an artist, I would always shut that down. But now, when I was doing Who Built The Moon? and when I was explaining that I got in the studio with nothing and just recorded and that was it and that’s being an artist… I was like, “Fucking hell. I better buy a scarf then and a fucking hat.” So I’ve only just recently accepted it and it’s a thrilling thing to be able to do.

What was it like when you first went out by yourself and there was an expectation among the crowd that you were going to play Oasis tunes?

It was difficult. And the smaller the gig the more you can hear, the more you can hear the guy shouting, “Where’s Liam?” or whatever it is. But then when you get to do the big arenas, you’re outnumbered by 16,000 to one and you’re looking at the set list and thinking, “Well, it’s just something you’ve got to work through,” because it’s going to define how it carries on. There were lots of shouting matches in the early days of High Flying Birds. You know, “You’re the guy that wrote the songs, why are you not fucking playing them?”

Did you ever capitulate?

No. The Oasis song list actually got less as the years went on. I started off playing Oasis songs because I only had one new album. So I was doing 21 songs and half of them were Oasis songs, but half of that half were B-sides. As I’ve gone along, I’ve got more solo stuff. [The Oasis songs have] got less and less. I’ve worked out the formula now. When I’m doing my shows, I’ll play what I want to play, but when I get to festivals I flip that on its head, because it’s not my crowd. The set list I drew up for the Glastonbury I was supposed to play and never did was very Oasis heavy.

I saw you when you played Twickenham with U2 on The Joshua Tree tour a few years ago. What was it like supporting them?

I loved it. It’s an older crowd, so there’s not as many people fucking shouting.

How have your ambitions changed since you went solo?

I’m not sure I have many any more. The thing I would like to have achieved, I’m not going to achieve now, which is an American No1 album.

Why do you say that?

Because I didn’t sign to a major and I don’t want to sign to a major. Every time I put a record out, I have to license it to different indie record labels in America, which is a ball ache and I’m probably selling myself short a little bit. I get offers all the time from the majors but I’m not interested because they want you to make Oasis music and that’s it. They want you to be a version of what’s popular. I’m sorry, but I’ve already done that and I don’t want to do it. I want this French girl to fucking talk in French in this middle section of this record. On a major record label they’d want me to change it and although I probably could get away with it because of who I am, I don’t want to be in conflict with anyone.

What are you most proud of in your career?

On the whole, I’d say the thing I’m most proud of is Oasis, because it means so much to people and has continued to mean so much to people that I still scratch my head about it sometimes. When we did the Supersonic documentary, along came another generation of fans and the flipside side of that is they have a specific version of Oasis that they want. I can’t give it to them and there’s a little bit of push and pull with that, but it became such a thing completely by accident. I’d like to say it was all by design, but it wasn’t.

I absolutely love the legacy of the band. I’d love it even if I hadn’t written all the songs. Initially, when a band breaks up, everybody says stupid things that you soon come to regret, but I don’t think I ever hated on Oasis. There is still kind of conflict with sections of its fanbase, but other than that, I fucking love it. I do love it. It’s a global thing. I couldn’t have asked for anything more as a songwriter.

Many people contextualise the end of the 1990s by the death of Diana, Princess Of Wales, the eventual disappointment of New Labour and Be Here Now.

Yeah. And the third series of The Fast Show. Yeah, it’s true, that’s why with the Oasis documentary, we stopped at its most glorious point, because who wants to document the fucking downfall of anything? It’s like Alan McGee’s film, Creation Stories – nobody wants to read about rehab. Anything about that period should come to a halt at Knebworth, because what became known as Britpop then got intertwined with politics somehow and that led to war and all that fucking kind of thing. The Manchester photographer Kevin Cummins was doing his book and I did an interview for it. He asked me a question about Britpop and nationalism and I jokingly said, “Ask Paul Morley and he’ll tell you about it.” So he did and Paul Morley literally blames Oasis for Brexit. I was like, “Wow. Fucking hell. That is particularly mad, even for you. But you can’t put too much fucking thought in what people like that say.”

With hindsight, how do you view the support of the creative industries by Tony Blair and New Labour?

Because Thatcherism had coloured all our lives, which was still prevalent with John Major, when Tony Blair came along and I heard him speak I thought – and I still think to this day – he was great. He’s the last person that made any sense to me. The third way, or centrist politics, was a new thing. I was like, “That is fucking really clever.” I started meeting them at various awards ceremonies. John Prescott was a bit of a cartoon character, but I thought the rest of them were all right.

Your thoughts on Cool Britannia?

I loved the 1990s and a lot of it passed through my kitchen. I liked Damien and Kate Moss was a great friend. It was a great period, a great moment in time. No one will ever admit it and every time I say this it gets picked up by the wrong fucking members of the press and turned on its head, but we were all Thatcher’s children, who got off our arses and did it for ourselves. That will get picked up by the Daily Mail, but what I mean is that this all happened in spite of Thatcherism. We were all on the dole, all on benefits and it must have dawned on us all that we were not going to get anything and that nothing would be given to us, so we had better go and fucking find a way of taking it.

To me, the 1990s was a lot of working class intellectuals who were not really connected, who all came through at the same time in politics, music, fashion, photography, art, sport. You know, young Muslim kid Prince Naseem was the greatest boxer that ever fucking lived at that point and it was like, “Who the fuck is this guy?” It just seemed to be a working-class thing. That’s what I took from it. Everyone I met was sound, more or less, and all the other players in the game, like Jarvis, Hirsty, everyone was fucking great. There was also a lot of Northerners, which is another unusual thing, which is not really the way any more. I do remember having one of those five in the morning cocaine conversations, when I was saying, “This fucking decade will be remembered as one of the greatest,” and everyone else being like, “Nah.” I felt at the time that this collection of people would eventually become the mainstream. I felt it was a moment in time, which I think it has turned out to be.

The 1990s now is revered as probably the last great decade when we were free, because the internet had not enslaved us all and driven the world’s neurosis to the point of fucking paralysis, where you can’t say or be or do or suggest or take the piss out of or be irreverent to anything or any fucking section of society. Whereas back then, it was fucking spontaneous. Everything was spontaneous and off the cuff, particularly in my life. I didn’t think about anything. And now everything is thought out.

I was watching the McGee film the other night and I was thinking, “That will never happen again,” as today there are too many spreadsheets. Back in those days, it was “Put it out, see what happens and move on to the next thing.” I don’t know what you felt about it, but that’s what I felt about it. I mean, look at all the great things that started in the 1990s. You know, magazines and fucking radio shows and physical things that people could hold, whereas now it’s all podcasts and fucking Netflix.

One of the few books about the period is The Last Party by John Harris, which, while being fairly comprehensive, is unremittingly negative.

Yeah, but he’s a c***. He says it’s awful because he’s a nerdy guy who was never involved in it. He wrote about it but he was never in it. He never came to my house. He wasn’t anybody else’s friend. He hated Oasis, because Oasis became popular. And he hated me because I agreed to go to Number Ten because his fucking mum and dad were fucking socialists and he never got invited. That’s the end of that. And Paul Morley’s the same.

People always said the 1990s were an echo of the 1960s, but that echo is pretty loud.

We watch Top Of The Pops every weekend at ours, as there is fuck all on the telly, and it’s got to the 1990s now and my missus was saying, and I can’t remember what act it was, but during the show, “There’s lots of gay artists and black people and women.” I mean, everybody was well represented in the 1990s, so where did it turn to, where nobody is represented now or the perception is nobody’s represented any more? Go back to the 1990s and everybody was represented fully and without thinking about it. Nobody was filling out quotas.

It’s also the last analogue decade.

There’s a great shot of Knebworth, taken by Jill Furmanovsky from the back of the stage. The stage is empty, but The Prodigy are playing and Keith has gone out into the crowd with a microphone doing “Firestarter”, and I remember the moment perfectly. He’d gone out in front of 125,000 people and you can only see him because he’s the only person with green hair. But the most significant thing is there isn’t a single person holding up a phone. It’s just the band in the moment with the people. That’s really significant, because now when you watch Glastonbury, it’s all fucking stupid flags and phones and people are trying to capture shit now and share it with somebody, but in the 1990s you had to be there.

What was the most euphoric moment of the 1990s?

I’m not really the kind of the guy that gets emotionally euphoric about stuff. There were points when I was kind of taken aback, like selling out Sheffield Arena, because four months before we were in a fucking rehearsal room. I was in a bubble for most of that period. I was writing and writing and that’s why the initial burst from 1993 to 1997 had so many fucking great songs, because I devoted my life to it. And then after that, I devoted my life to fucking spending it and snorting it.

In the rock canon top ten, what number are Oasis? Top five?

I used to always put us at a solid seven, the band and all its glory. I came up with it one night on the tour bus: The Beatles, The Jam, The Sex Pistols, The Smiths, Happy Mondays and The Stone Roses go together, the Stones and then us.

And how good is (What’s The Story) Morning Glory?

That record bends my head. They were just demos. I didn’t even finish the fucking record when I went in. That’s why half the songs on the record have got one verse and one chorus, because I was like, “Fuck it. I’ll just do when I get there.” Of course, I never did. I prefer Definitely Maybe, because to me that is Oasis. But Morning Glory, I mean, it’s an amazing thing. I don’t know where I’d put it, but I’d put it up there, though. It’s continually voted in the top two of all time, so I’m not going to argue.

Do you still hate Be Here Now?

I’ve grown a bit more fond of it over the last few years, but when I think of that record I think of the chance that I missed to really fucking cement it, to send our legacy into the stratosphere. On the previous two albums, I devoted my life to these songs and to getting it right. And on Be Here Now, I became quite wealthy and I struggled. I would never have admitted it at the time, I probably didn’t even realise at the time, but when the light of the musical world is shining somewhere else and you’re kind of in the shadows writing these great songs, I prefer that, but when the light is then shined upon you and everybody’s waiting for what you’re going to do next, I kind of weltered a little bit.

I was having a great time on drugs and the songwriting became secondary and I remember doing the demos and then bringing them back and playing them to everyone. I was expecting somebody to say, “Yeah, they are OK,” but everybody went mental and said, “Fucking hell. These are amazing.” And, honestly, I remember going home from a meeting and thinking, “It can’t be this easy. I’ve done virtually nothing on this fucking record.” I literally went away on holiday and fucking didn’t really put that much fucking time and effort into it. And now everybody’s saying it’s going to be bigger than Morning Glory. And I was like, “Man, if it’s this easy I’m in trouble.” I don’t like any of my guitaring on it. I know the lyrics are fucking wank. I mean, my ego had got the better of me, I think. I was like, “Yeah. Fuck it. This will do.” I was expecting for somebody to say, “Yeah. It’s good. But you might want to go and finish them off.”

But then when I got back to England, everyone was saying it’s the best thing you’ve ever done and I thought, “Fucking hell. Maybe it is.” It took me from that songwriting episode until well into the 2000s to recover, because I was chasing my tail and trying too fucking hard. Some of the songs had become a little bit of a parody. Like, “Little By Little” was great but I’m not too keen on the recording.

Finally, would that decade have happened without drugs?

Were they important? No. Were they good fun? Yes. Did everybody have enough money to afford to buy a lot of them? Yes. And I’m not just talking about my circle of people. I think it probably would have happened without drugs. Yeah. I mean, cocaine, which is what we’re talking about here…

I mean the decade started with everyone taking ecstasy.

Yeah. Fucking hell. What a drug. If that had gone on through the 1990s, it might have been a little bit groovier. Cocaine, it’s not the most creative drug in the world. And, again, it’s not unlike the internet. It drives neurosis. And you’re just talking out your fucking ass. I mean, the reason I packed it in, was because I had enough of the 5am conversations about the pyramids and fucking this, that and the other. It was all fucking nonsense. Everything I ever did on cocaine would have to be redone. Be Here Now was written, recorded and performed on cocaine and if you’re into that kind of thing… I meet so many kids and I signed so many of those covers and they’re always on about this album and I’m like, “If you love it, fucking great.” I can only have my opinion and that’s it.

Source: GQ Magazine UK

Photo: Getty / GQ